No subject was too small for Australian painter John Brack, who at the height of his career in the 1950s-1960s became one of the nation’s most beloved artists. He was raised on the outskirts of the Melbourne CBD in a conservative household that shed away from artistic decor, this was reflected in his upbringing that lacked exposure to the creative arts. It was until his late teenage years that Brack frequented the state library, as many artists of this time did, and like them he enrolled in evening classes at the National Gallery School where he studied five nights a week from 1938 to 1940 before enlisting to serve in WWII. As it shaped many young men and women, the second world war was an undoubtedly formative period for Brack who was in his mid twenties, the experience altered his perception and gave him a natural introspection on humanity’s capabilities. After returning from the war and graduating from gallery school, where he met his wife Helen Maudsley, he began working at the National Gallery of Victoria. The direct and consistent access to the gallery’s collection greatly improved Brack’s art historical knowledge and introduced him to the cipher of Australian art history - painting. The years that followed the war saw Australia’s post-modernisation to be a key focus in many artist’s work including Brack himself. Although, many failed to capture the tensions at the edge of a new society and the failure of the romantic concept modernism could deliver. Brack’s career in painting was a form of aloof social commentary which was interpreted as satirical and ironic, described as drawing or cartooning the caricatures in and around his life. Alongside the experience of the NGV institution, many literary sources fashioned John Brack’s thematic exploration of the human condition, theorists such as Henry James, Wyndam Lewis and poet T.S Eliot provided sources of modern vanguardism. Australian artists referenced contemporary English, European and American literacy and art for the ideological forces in order to pick apart a truly Australian artist - literary identity crisis. Formalist themes ran through his work over the next two decades, they followed the path that many artists pursue - portraiture, nudes and landscapes. Supporting these works was an air of disdain to the post-war provincialist and nationalist society Melbourne and the rest of Australia was becoming.

Australia’s historical displacement with art and culture during the 1930-1960s led to self-conscious art phases wherein cities like Melbourne and Sydney became battlegrounds for the future of art. To contextualise the period Brack worked in, there was a rising provincial anxiety of Australia's geographical isolation which became apparent when European and American art exhibitions would tour and visit Australia’s main cities, leaving an imprint on our major contemporary artists. Ian Burn, an artist and writer working concurrently with Brack theorised the historicisation of art objects as cultural necessities that “reflect a tendency towards populism”. The notion of revisionism in the Australian art scene during the late 1950s and early 1960s was noted as an artistic vanguard. The developing international trends of abstraction caused a rupture in the art scene and a struggle between figurative and non-objective art, Melbourne versus Sydney. Critics saw abstract styles to be a solution for “contemporary art’s dilemma”, whereas a group of Melbourne artists, named the Antipodeans, initially believed otherwise. John Brack’s short affiliation with this group was pivotal, he exhibited alongside the Boyds, Charles Blackman, Robert Dickerson, John Perceval and Clifton Pugh, all with their various international and local relations. It was predominantly a market-driven aesthetic in the art establishment at this time, which specifically catered to bohemianism of contemporary artists. Artists like Dickerson and Blackman also depicted the human condition in their personal styles, John Brack was in league with their practices rejecting the surrealism of the circles such as the Angry Penguins. Published as a foreword to the Antipodean Exhibition held in the Victorian Artist’s Society’s galleries in 1959, Bernard Smith accounts the threat to figurative painting and was simultaneously able to see the agonistic hope in its future. Smith deemed it worthy for artists to take into consideration their immediate surroundings for inspiration. Importantly, these Australian contemporaries were loyal to their art and loyalty, which Bernard Smith notes at the end of the Antipodean Manifesto, requires the defence of the image.

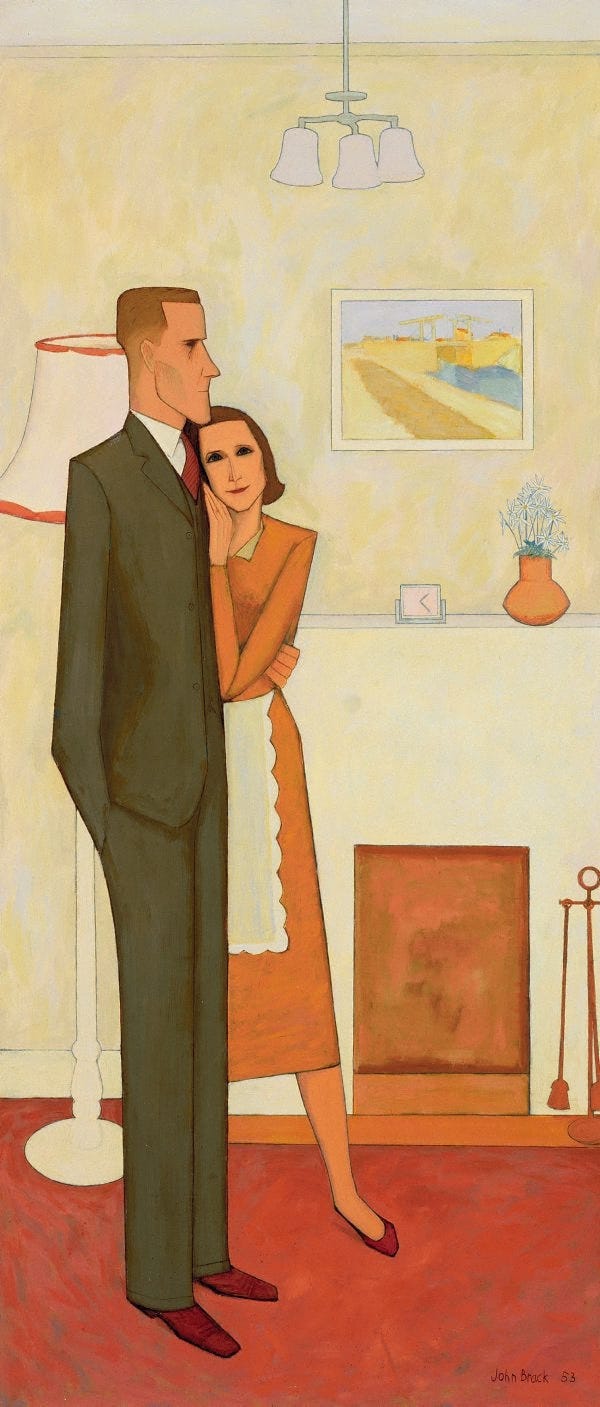

The New House painted in 1953 begins our exploration into the foundation of Menzian Australian culture seen through John Brack’s eyes. Painted with oil on a hardboard, this narrow painting with dimensions reaching 142.5 x 71.2cm is a glimpse into the empty lives of a couple’s new home. Staged in the era of political history during the Australian post-war economic depression, the 12th Prime Minister Robert Menzies was transforming the quality of life for middle class Australian workers. At the centre of this ideology was the notion of being a homeowner with a family and full time job in the city. Brack clearly depicts the outset of this way of life in all it’s dull and disillusioned glory, the couple are embraced but only one is engaged with the scene, the wife is connected to her partner with her head on his chest and stares into the audience with large hollow eyes and a skinny smile while her partner is absent and staring into the distance showing his stricken profile. In the background is a variety of symbols that combined together form the home they reside in, Robert Menzies describes this domestic scenario as “the foundation of sanity and sobriety”, a lamp as tall as the man, a vase with dry flowers, a small clock showing the time 1:25pm and a hanging painting. Interestingly, one of John Brack’s first artistic inspirations was the Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh, hanging above the mantelpiece is a reproduction of van Gogh’s 'Langlois Bridge' (1888), an absurd and ironic detail of decor. The outfits of the two characters represent their roles in society, the male is cloaked in a dark grey tailored suit with a red tie and matching shoes, while the woman is still flaunting a white waist apron indicative of her domestic activities, they both signify ideal exterior and interior lifestyle choices. One can view this painting as an advertisement for new homeowners or as pure deception. The application of paint pervades a sense of flatness to the scene, the objects are hollow, the fireplace empty and lamps are vacant, their lives are sparse and unfulfilled, lamenting romanticism, all masked by the wife’s smirk.

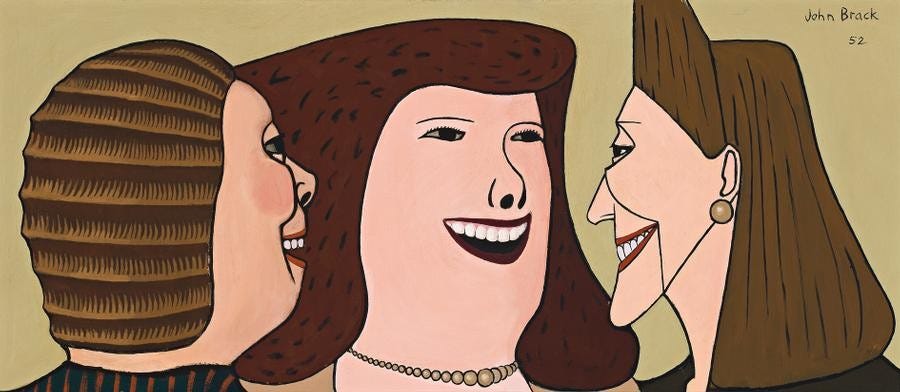

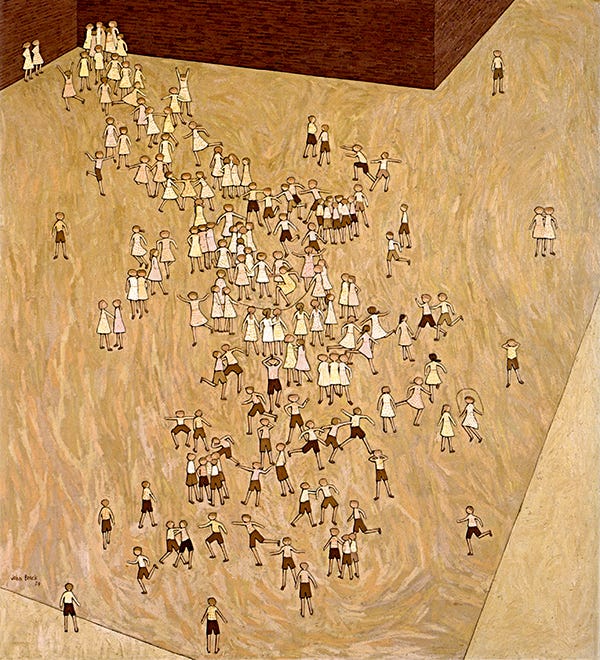

A secondary key motif that spans throughout many of Brack’s paintings is the documentation of people in various stages of their lives. Near the end of the 1950s the painter was a father to four children between the ages of 5-10, his experience of fatherhood and nostalgia to his own upbringing was prevalent in paintings such as ‘The Artist’s Children’ (1959) and ‘The Playground’ (1959). The universal experience of childhood was a figurative and uncomplicated choice of subject matter, their unpredictable and precarious actions fueled the artist to record their lives in paintings and drawings. He observes and comments on the fascinating dynamics of crowds, notably seen in ‘Collins Street 5.pm’ (1955), drawing distinct comparisons between the social dynamics of children and adults and how they interact with one another. In ‘The Artist’s Children’ his four young daughters fill the extent of the canvas, their oversized and underdeveloped heads like large pale dishes and matching striped tops all portray different emotions. The central face is laughing, her hair is unkempt, eyes squinting and teeth baring as she cracks a joke, the older sisters are not impressed, their mature facial expressions scold the young girl. Very similar to the composition and relationships portrayed in an earlier work of three middle aged women named ‘Three Women’ (1952). John Brack’s portraiture includes the subject, the artist and the viewer all with a sense of detachment from one another, we view works like ‘The Playground’ from an aerial perspective, looming over the crowd of children during a lunch break in the school playground. This style of painting is derivative of Dutch Renaissance paintings such as ‘Children’s Games’ (1560) by Pieter Brugel the Elder, where a large landscape of people are all in focus with crisp outlines. Scenes in the Brack’s schoolyards and Brugel’s work are legendary for their detail, one can zoom into a small part of the painting and unveil a complex entanglement of lives.

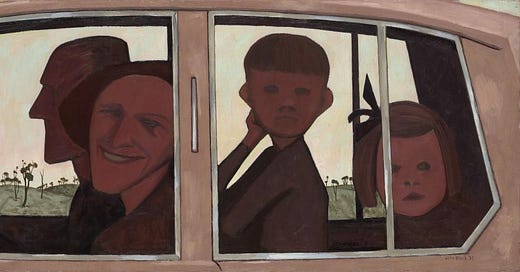

In a preparatory drawing for ‘The Car’, the artist names the sketch ‘to the hills’, when the painting is complete in 1955 we see a baron landscape with rolling hills and sparse trees through the car window in the background. The activities families were urged to undertake for pleasure outside their jobs consisted of car trips to the Australian outback and seaside visits, traversing untamed landscapes and exploring a life outside of the city was regarded as a form of leisure for the 9-5 working class, this greatly contributed to leading an Australian life. John Brack himself lived a conservative life even during the height of his success, what was more interesting was the recreational activities of people around him, he was a keen observer of people indulging in window shopping, betting on racehorses, purchasing automotives, dance and gymnastic competitions. Many thematic choices were influenced by a bygone era, Brack’s racehorse and ballroom dancing series were a fate of the art in the age of modernism’s decline. Parallels between Brack’s paintings and contemporary advertising are combined to form the social experience of Australians. In the accompanying book for the John Brack retrospective exhibition, writer Robert Lindsay’s essay ‘Observation on the Observer and the Observed’ elucidates the important artworks of shop front windows. Lindsay remarks on the “anthropomorphic objects” In the windows, predominantly displays of surgical instruments, butchers, fishmongers and even prosthetics were painted as if models decorated in gowns. Brack seamlessly transformed the mundane object into a glimmering consumable item. ‘Inside and outside (The shop window)’(1972) shows a large figure with an oversized suit jacket peering into a kitchenware shop where sharp carving items and clamps are splayed out on the floor, the rest of the shop seems empty and is covered by the dark reflection of the man. Furthermore, these paintings were metaphorically reflections of the self, with the viewer becoming the subject staring into oneself, the consumer here is being consumed.

The final decades of John Brack’s career were impacted by the dissolutions of Modernism due to rapid cultural changes. Australia’s desire to keep up with the rest of the world was a weakening trait, transculturalism brought many artistic themes through the nation in the late 1960s and 70s with art “ideas travel[ling] faster than ever”, this eventually led to the death of Modernism and the birth of exhibitions like the ‘The Field’ in 1968. The abstract artists in this exhibition formed a new generation of contemporary relevance, somewhat leaving Brack behind. For most of his life Brack’s intellectual journey was tied down with his figurative and conservative tendencies, he believed to have reached his technical completion by this era and turned to teaching at the National Gallery School and subsequently resigned as a secretary and treasurer. Fewer paintings were produced during his later years, these works had some changes to personal style with less harsh outlines and popular culture references, although his later works couldn’t maintain cultural relevance. Despite Brack's 1970s conclusion, this essay reveals the essential periods of his legacy which had great impact on the advertisement of Australian living.

Readings:

Art Gallery NSW. “The New House.”John Brack collection, Art Gallery NSW. accessed 09/05/21: https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/192.2013/#bibliography

Blackman, Charles, and National Gallery of Victoria. The Antipodeans Revisited : Melbourne Figurative Artists of the 1950's.Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria.1976

Brett, Judith. Robert Menzies' Forgotten People. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing, 2007.

Butler, Rex., and Institute of Modern Art. Radical Revisionism : An Anthology of Writings on Australian Art. 1st ed. Fortitude Valley, Qld.: Institute of Modern Art, 2005.

Burn, Ian. Dialogue. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1992.

Grant, Kirsty., and National Gallery of Victoria. John Brack. 1st ed. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2009.

Hansen, David. "‘This Broken Jaw’: T. S. Eliot, Ern Malley and Australian Modern Art." Australian Humanities Review, no. 64 (2019): 62-69.

Rothnie, Susan. "The Case of the Vanishing Mediator: Seventies Art in Australia." Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 12, no. 1 (2012): 140-60.

Smith, Bernard. The Antipodean Manifesto : Essays in Art and History. Melbourne ; New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.