Evie Poggioli

Like Wading Through Honey, Suicidal Oil Piglet: The Womb

12 Apr – 3 May 2025

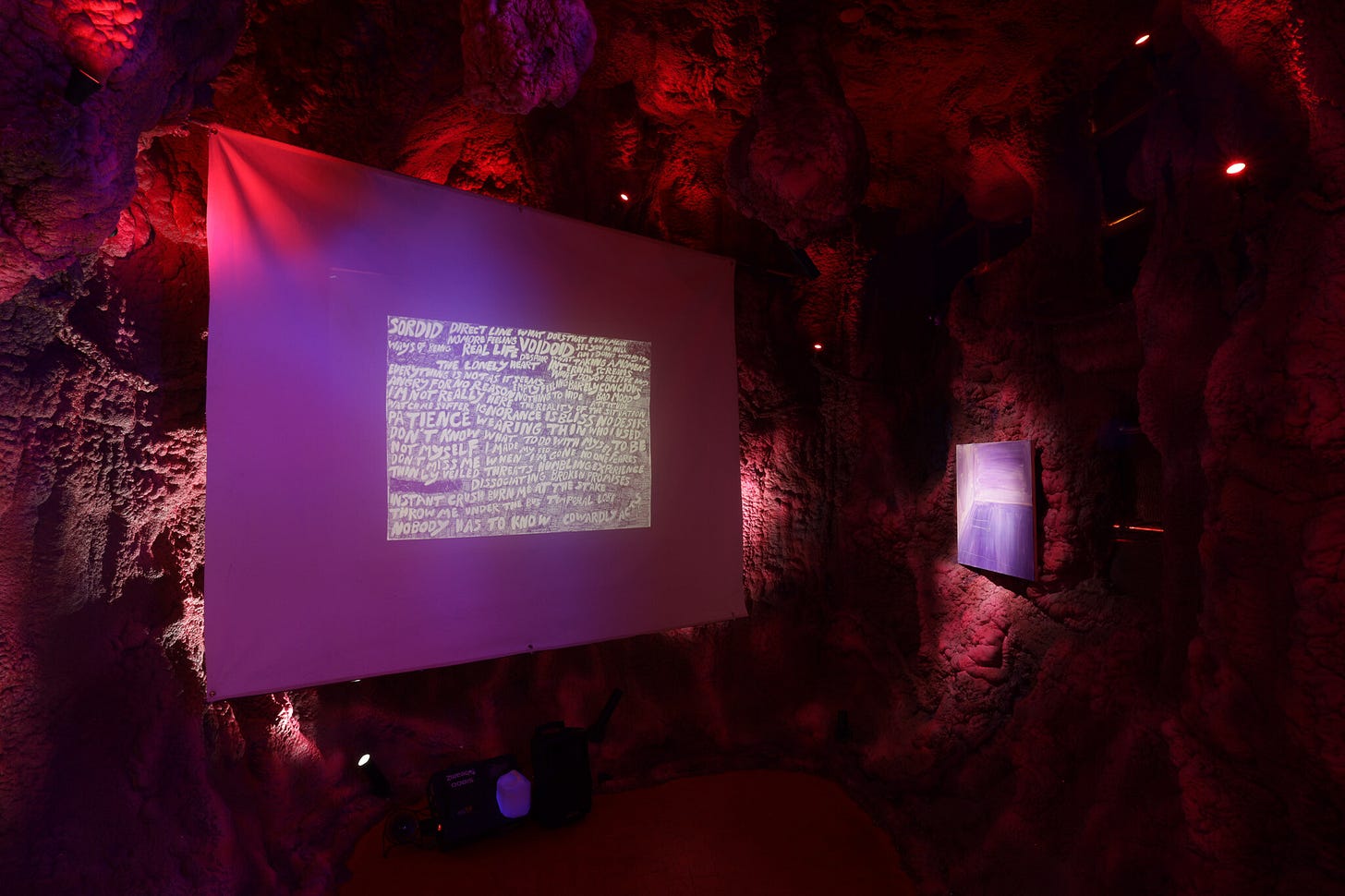

A leap in the dark from the easterly lung: falling briefly, a sudden landing in the Heart Chamber/Cunt Chamber. Enormous soft velvety warm damp walls rounded ridged pulse gently. Your whole body is squeezed up and down; between pulses you can clamber around holding onto the ridges. Each ridge you touch emanates a flash of brilliant coloured light. It is slippery, the muscle walls expand, contract, push you slightly up or down. You may doze in the strange rocking.

– Carolee Schneemann, “Body Parts House” (1968)

Weeper, Screamer, Bloater, Physical Wreck, Craver. These words feature on a 35mm slide next to an image of a yelling woman with her hands in the air—one of many projected slides at Evie Poggioli’s solo exhibition, Like Wading Through Honey, at Suicidal Oil Piglet: The Womb. The exhibition is a challenge to the institution and its mental namesake. Through a slideshow narrative and surrounding wall works, Like Wading Through Honey represents the externalisation of inner illusions. A collection of intense images and notations creates an aesthetic that mirrors an individually fragmented mind. It’s megavisual. It’s mental illness reframed as pleasure to explore the depths of vanity and its internalised effects. At once uncomfortable and didactic, the exhibition bears witness to, and is a testament to, psychic pain. At The Womb, older diary-based works are presented alongside recent drawings created in the psych ward. From her wax candle paintings to bubble word drawings, a common thread in Poggioli’s art has always been incandescence. This new show meets us in the middle with a lecture on the heart.

I begin to absorb information from the slideshow. The set-up is an old 35mm slide film projector with an upright wheel of individual picture slides. It is projected through a glass window—part of the space’s existing architecture—and onto a screen. Underneath the screen is a large speaker and a fog machine. All of these elements form the artwork Like Wading Through Honey (2025), the show’s centrepiece. The never-ending slide show clicks away at a paced beat; some images are found, others are repurposed, and most are original. They largely fit into the themes of education and language. Evie isn’t the teacher, though the voiceover has a God-like cadence. She has used acetone wash and a new marker to reconfigure old slides. Capitalised words flash up at us, for example, evil, petty, crush and rage. My relationship to the meaning of each word starts to shift. I link my self-conscious thoughts to the patterns that form throughout the slideshow: themes of body image and fashion, of the fragmented artworld. I’m mostly fixated on the blackened, torn slides, with their punctured holes and deep scratches. They are rough and ugly, but also beautiful—qualities that remind me of Poggioli’s 2021 solo exhibition at Guzzler titled Black Paintings. On the black painted canvases, those works also featured rough textures, only visible by incandescent light. I try to distinguish which images are found and which are her psych ward drawings, but it’s hard because they all fall under this blurred display of the mind.

While the slides cycle through, a seventeen-minute spoken piece plays through the speaker. Poggioli exhales deeply between passages while she describes lying on her side: “hearts together, broken open, messy love, happy tears, quiet mind, running away from oneself until they calm down. me, you, mad at me.” Suddenly, the fog machine starts gushing out smoke; the sound is so loud that it drowns out Poggioli’s voice. After a beat, it stops. She continues: “something weird, excessive love.” Some phrases overlap with each other, and at other times, Poggioli mispronounces words, but her reading maintains a grace. The audio represents an overthinking mind. It questions what sickness feels like to others and how it feels for Evie. The spoken word undergoes analysis of the “bendable boundary” of the artist as myth. She mentions 666, she repeats “seroquel” three times, she talks about a spell of fate. Kathy Acker is cited, a reference fitting to The Womb: the signal and the signifier/Blood and Guts. Acker’s literature also excavates the kind of psychic pain that rambles into infinite destruction, which perhaps mirrors the feeling of being stuck in the trance of Poggioli’s slideshow. With deep focus, I’m falling further into Poggioli’s world, letting myself through the broken down walls of love’s company.

Essential Oil Sleep Blend (2025) is installed at the back of The Womb, almost hidden by the spilly walls. Featuring a thin line scratching of a double bed in the corner of a room, the painting has a numbing effect due to its washed-out purple acrylic background. A chronology of work involving rooms can be traced back through Poggioli’s practice. A Narrow Road Leading to my Bed in 2018 at Suicidal Oil Piglet and Being Evie Poggioli at Centre d’Editions three years later also included a similar bed to the one in The Womb. These became pseudo-archival shows used to record Poggioli’s world. They centred on imagining desire in the passage of the artist’s mind and then actualising those neural corridors in a gallery. The paintings in the Narrow Road show were meditations on Poggioli’s private space. The dark paintings contained words like “fucked” and “bored.” The same bed painting was reinstalled in the Centre d’Editions show, where Poggioli replicated her apartment by printing off life-size scans from every angle of her furniture. The gallery floor plan was redesigned as a set to her real life, filled with her possessions as they would be found in her home. Another standalone artwork in The Womb, Mirror Box Head (2025), depicts a sterile cleared out space. This painting exists outside of the fleshy space, on a white wall near the entrance. The grey acrylic painting is of a liminal tiled room, I think psych ward-related, but it could also just be a depiction of an empty mind. Mirror Box Head (2025) and Essential Oil Sleep Blend (2025) contribute to Poggioli’s preoccupation with the surveillance of her secluded spaces.

Thank God for Mental Illness is the title of the 1996 Brian Jonestown Massacre album that featured on a skateboard artwork at an early Suicidal Oil Piglet group show. When looking through old shows at this space, many of which Evie was involved in, I can see patterns of archiving fetish commodities. This show seems only to be able to exist in a space such as a womb, a place where love is central. The Womb takes on the trends of surrealist exhibitions and re-imagines them to fit with our highly libidinal economy. Evie contributes to this by reading out loud, “Nothing comes from nothing, simply entertainment, simply existing parasitic relationships.” Like Wading Through Honey marks an important moment in Poggioli’s generation of artists. They’ve found the fetish in the illness, in the parasitic relationships of the art world and in the internal artworks. Thank God for mental illness, for a time to be perceived. Thank God the patient’s art is spiralling and disorganised; it has resurrected itself as ubiquitous and abstract. No one entrusts us with love’s neurosis quite like Evie Poggioli, who is walking around knee-deep in womby molasses.

written for MeMo review https://www.memoreview.net/reviews/like-wading-through-honey-by-margarita-kontev