Contents

Curatorial Intention

Part 1: The Database

Part 2: The Glossary

Part 4: The Interviews

Diego Ramirez

Megan Cope

Rohan Rebeiro

Dylan Martorell

Part 4: Visualisation

Reference List

Curatorial Intention

Let's consider the vacuum sealed ambience felt in a space of art that is separated from the bustling world outside, where a conscious sound insulation sanctions a meditative state to prepare the audience for culture viewing. Oblivious or not to the conditioning, they become tranquillised and assimilated alongside the silent art, by being far removed from the exterior one can forget the outside tumult and is subjected to just another aspect of the gallery soundscape.

Preventative measures are taken to rescue galleries and museums from disruptive noise pollution caused by traffic, construction, weather conditions, human conversation and movement in order to begin with a sterilised space. The research this project will undertake dissects the feeling of isolation and detachment from reality upon entering an art gallery, in a world full of commotion I will document how the transition into a solemn gallery can evoke an equal sense of religiosity and self-consciousness. This companion will guide you through the methodologies of enhancing your next visit to an exhibition, through data collection, on-site observations and conversations with practicing artists, writers and curators, the manual will provide critique on the institutional decisions made to manipulate a visitor’s experience.

This research project asks everyone to become a critical listener in the space of art. The auditory behaviours of an exhibition space aren’t only sensed by the ear, but are absorbed through sound wave vibrations affected by architectural form. To realise these outcomes within the densely art active vicinity like Melbourne/Naarm, field recordings will be translated into condition reports for a publicly accessible digitised catalogue. Preserving the sonic encounter of the interior and exterior spaces to investigate the shifts in soundscapes of varying geographical locations, from inner city institutions and backyard shed artist run spaces to regional sculpture galleries.

The third part entails a series of interviews with practicing artists, writers, musicians and curators who are conscious of space and sound when working with their art forms. I chose the four interviewees for their specific practices and relationships to audio/visual based work, they provided me with new perspectives on impacts of sound from first hand experiences. The conversations around location scouting, sound conscious artwork on an international scale, environmental impacts of sound and more will further enhance the thoughts around the installation and curation of soundscapes.

The final section of the manual conceptualises and consolidates the research project. I ask you to consider the perfect gallery space and are you at peace with it? The conclusion is obscure and imperfect for its unattainable sensitivity to ideal future art spaces.

Part 1: The Database

This collection of field recordings is an ongoing project begun in 2021, where I sonically mapped out the interior and exterior spaces within art galleries and museums exploring the acoustical characteristics that make art spaces unique sites to visit. The .wav files are free to download, they belong to the internet now.

share - circulate - absorb - visualise

Aimed to be both a collaborative and personal project, while listening to the recordings I ask you to consider these questions :

How do the internal and external sonic environments of art sites differ around local and neighbouring contexts?

What is important about the geographic location of Melbourne, mapping a densely art active area, is there a sense of competition between Melbourne CBD and suburban based galleries?

How does the lack of sound conditioning change the experience of viewing art, by consciously muting an art space, what are the consequences to the artists, artworks and spectators?

When walking into a gallery, how do you see yourself - simply a spectator? or a part of the room’s attributes? Perhaps in slight ways, your movement impacts others.

Access the database:

https://listeningcompanion.files.wordpress.com/2021/10/the-database.pdf

Part 2: The Glossary

A Brief Dictionary of Sound and Spatial vocabulary

Decibel (dB): a degree of measuring the intensity of a sound

Aural: relating to absorbing sound

Acoustic: the sense of hearing / the quality of sound transmitted through a room / a branch of physics concerned with the properties of sound

Sonic: relating to sound and sound-waves

Audio : sound when it’s recorded and transmitted

Timbre : the frequencies that compose the individual sounds

Pitch: the degree of highness or lowness in a tone

Acoustic ecology : the space which generates sounds

Soundscape : the combined sound that create the atmosphere of a space

Ambient : relating to the immediate surroundings

Noise pollution : the harmful levels of noise

Multi-sensory : using different senses

Resonance : the quality in a sound of being deep, full, and reverberating

Reverberate: a sound repeated several times as an echo

Composition : an orchestrated collection of sounds

Dynamics : how loud or soft the sound is

Tempo : the speed at which the sound is moving, measured in BPMs

Polyrhythmic/cross-rhythm : simultaneously combining various rhythms in a composition

Part 4: The Interviews

Diego Ramirez

Diego Ramirez is an artist, writer, editor and curator in Melbourne/Narrm. His fantastical art practice ranges from performance, video and photography, with images referencing the supernatural. Currently Ramierz is the gallery manager at the artist-run-initiative SEVENTH Gallery in Richmond and is also the Editor-at-Large at Running Dog, the Sydney based art magazine. On September 27th, we met up over zoom for an evening video call to chat about his artistic and curatorial perspective on installing works.

MK: Talk me through your art practice and curatorial position

DR: I’m an artist and a writer, working in the arts. My art mainly deals with otherness and I look at how that manifests in different sites of culture such as the moving image. A nice way to read my work is as someone who’s turned their back on that 2015-2017 ‘Dear White People’ era of wokeness, the period of Buzzfeed articles that write about angry POCs, so I really feel like I work away from that and got into things like religion and the occult – looking for a deeper meaning. That’s an honest way to look at my work, I deal with imagery of vampires and Virgin Mary. I’m also the director of Seventh Gallery, I don’t curate as such but I guess I participate in the art world by shaping an area of practice which is based around emerging artists who come from experimental backgrounds, so that’s mainly what our calendar is made out of. I also work at Running Dog, in Sydney, as the editor-at-large, working with similar styles of experimental practice.

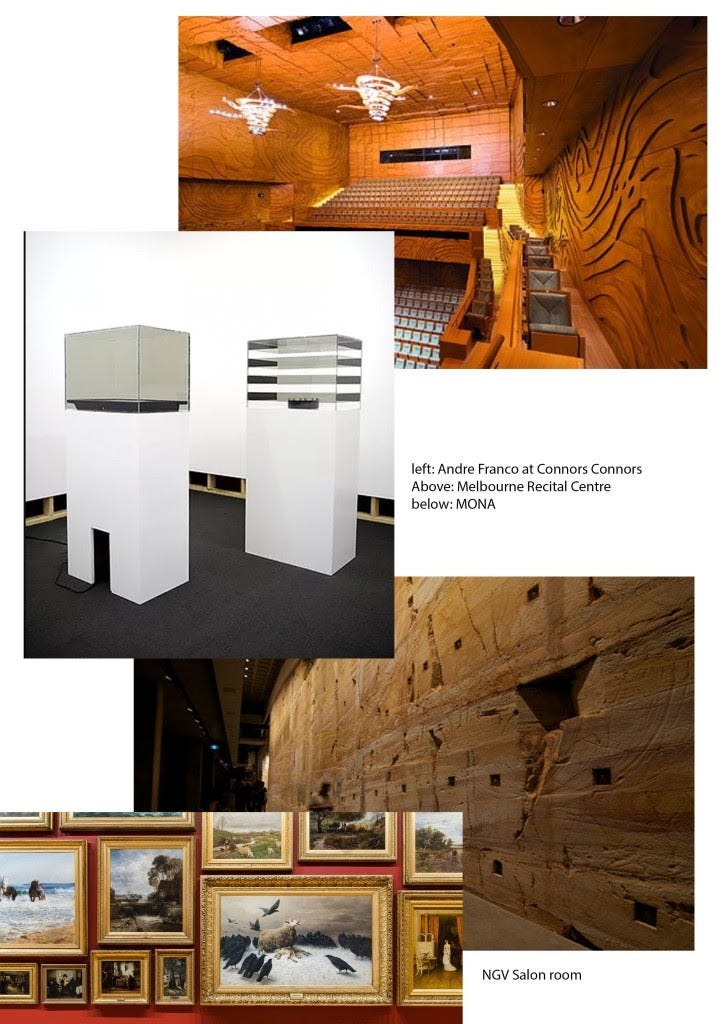

MK: As the gallery manager of Seventh Gallery, can you talk me through the space, describing the atmosphere and its volume?

DR: Well we just moved, so we used to be on Gertrude Street and we moved because of COVID, so we reopened again this year in Richmond, just off Church Street. It used to be a maternal health centre, so our new space is very similar to Bundoora art centre, so quite a domestic space, in the sense that it has an art deco ceiling, but we’ve installed the white walls. Basically we have three gallery spaces, two studios and one big garden area.

MK: Have you seen Connors and Connors, the small two room space in a town hall in Collingwood?

DR: Yeah so they’re also subsided by the City of Yarra, and yeah they did such a great and wacky job with that space.

MK: What kind of area is the gallery situated in, and how has the gallery prevented outside noise from entering, or is it embraced?

DR: I would say maybe more like a busy road area, so it’s on Church Street, and we have a police station next door, which is culture. In terms of noise, we definitely haven’t insulated the space but it hasn’t been noticeable and you know we’ve only had one show really and that was only open for about two weeks, then lockdown happened.

MK: In your practice, when working with video and performance art, which inevitably deal with the production of sound, what sort of spaces do you seek for that can best accommodate?

DR: So I work in gallery spaces across the board, none of them are really adapted for sound, not many gallery spaces have carpet, they usually have really bad reverberation. The best sound experience I’ve had is showing at cinematic spaces, like ACMI and other film festivals, cinema rooms are better sorted of audio experiences. My experience of showing in cinema rooms has been involved with experimental film festivals like Channels at ACMI, rather than video art.

MK: I’d like to talk about your performance at the Gertrude Contemporary VENTRILOQUY Lifelessness showcase, where you sat on top of a coffin, sipping a slurpee, strumming songs about an audition tape for a Mexican Buffy the Vampire slayer, standing at the back of the room it was dim and sweaty and the red neons cross on the coffin made it look like an interval show to a strange club. Do you remember what that performance felt like in the West Space offsite location?

I remember they were looking for a more diverse cast, so I had this perception that if I perform something like that in front of a crowd of white progressive liberals they wouldn’t know if they were able to laugh or not.

MK: I definitely laughed, so what are you working on at the moment?

DR: Mainly writing, I’m working on this new series which will be postponed until next year. The show was a series of works called Troll and they were inspired by the darkness of the media, especially social media. How woke culture on instagram resembles a lot of harassment and trauma and the narcissism of woke anonymous culture.

I’ve also been writing these letters to a friend I lost to migration. When I was a child he moved to Las Vegas and I never saw him again, he just disappeared. So I’ve been writing these letters, they’re not real but they address him. Who knows where he is, imagine living in Las Vegas it’s so bizarre.

Megan Cope

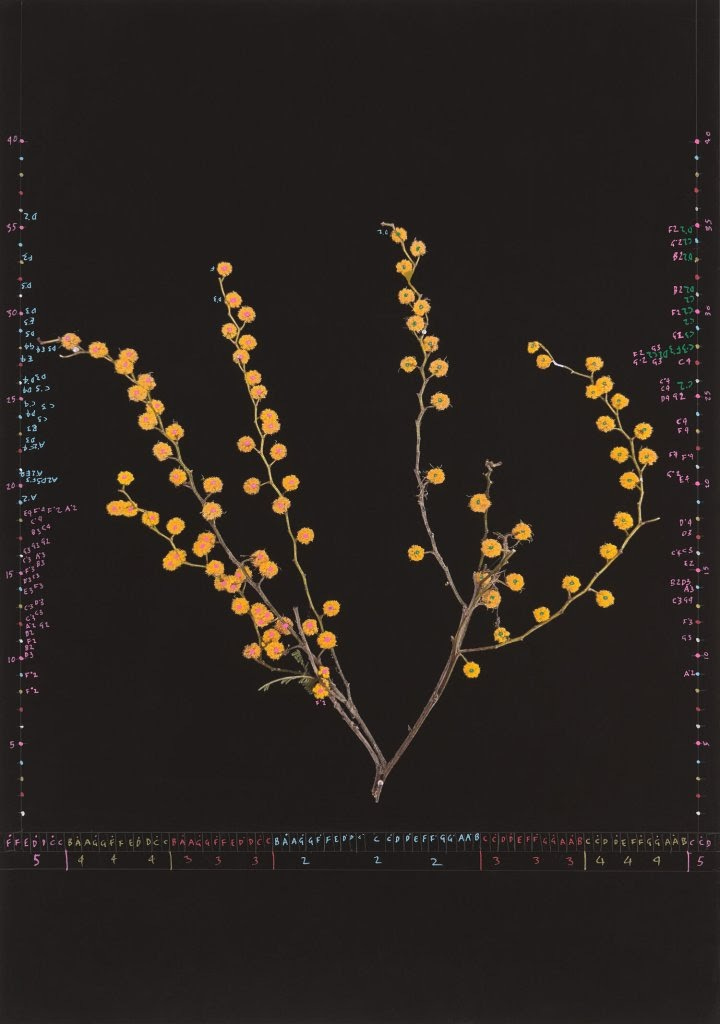

Megan Cope is a Quandamooka artist from North Stradbroke Island in Southeast Queensland, she is a current member of the Brisbane-based Aboriginal Art Collective proppaNOW. Her site-specific sculptural installations, video work and paintings investigate issues relating to identity, urban and environmental ecologies, mapping and collecting practices. We met up over Zoom on a Monday morning to talk about a recently exhibited artwork and the symphony of ideas created through collaboration and community.

MK: I came across your work when I was doing an internship with Liquid Architecture’s archives, and ‘Untitled (Death Song)’ 2020 came up, and I’m very fascinated to discuss the installation. Can you talk me through the ideas behind this work.

MC: Well to be honest I can’t believe how much that work has connected with people and I’ve struggled to keep up with all of the interesting conversation with the what and why, so it’s been overwhelming and affirming.

I feel very sensitive to what’s going on in the world, I feel very alarmed by the state of shock and imbalance and I’m also alarmed at our apathy and inaction to personally go out and start looking after the bush and teach ourselves about the bush or make connections with Aboriginal people that are meaningful. I wanted to make a work that I could be certain would enter the body and affect the spirit and the soul and I felt like sound is so powerful in that way. I wanted to try and highlight how our fatigue may also be because of all the white noise in the industrial environment and in the city environment and also noise on the internet, on the screen, all that over-stimulation. So I wanted to compete with all of that in a way to hopefully have some reach because it’s very difficult to connect with people these days.

The work was a way to talk about important issues, like extinction, extraction, violence, traumatised landscapes.

MK: I can see sound being used to connect to others, whether it be a vibration or a sound frequency, it’s able to communicate emotion which I experienced when watching the recording of ‘Untitled (Death Song)’. In the accompanying text published on Disclaimer Journal there are some instructions during the performance to practice deep listening, like focusing on a sound moving through space. What does this feel like in a gallery context?

MC: Well, I actually haven’t seen the work activated, because both times it’s been activated I’ve been in lockdown and so I haven’t seen it, I really hope I do get to see it activated. But the video capture of the Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art (2021) rendition, I think is really strong. It’s going to the Tokyo Palais in Paris next year because one of the curators was there and was very moved by it, lots of people have been moved by it and there’s been so much incredible feedback so I guess to make a work like this and have this opportunity and to have people be opened to the experience.

MK: There’s something about a performance that makes the audience completely attentive and self aware, it’s very different to walking through an exhibition because you have to sit and stay for the duration and absorb all of the information. Was there any thought of displaying this work outdoors?

MC: We did talk about that, but the rocks were very important and critical in providing the tone and the pitch of the strings for when they are played so it would be quite dangerous. The rocks are quite heavy and you can’t have the public just being able to go and swing a rock on a string that could snap. We did talk about potential activations outside in the lead up to the Adelaide biennial with Lee Rob, the curator of Monster Theatres.

I have a lot of ideas swirling around, and sometimes you get the right invitation to make something that's going to really apply to the whole ambition of the theme and the conversation that the curator is hoping to have and we were able to do that with Monster Theatres. So we just did it in the gallery. I'm looking at the arrangement and at more performance opportunities but I’m more interested in assembling the sculpture and doing the social development – working with First Nations composers or community members. This work is very much about the call of the (yellow eyed Bush Stone) Curlew, and we have a relationship with that bird and it’s very specific to Quandamooka People and other people as well but in this instance I really needed to rely on that. If I’m in Melbourne and I’m going to do something on Wurundjeri Country then a process might start being formed where they talk about animals that are important to them that have important messages and maybe we can compose and practice the replica bird call – I think that’s really important and it think I’ll continue to do that.

MK: It will be interesting exhibiting this work all the way in France, how do you think it’ll be received?

MC: This is where the performance aspect is really critical and the activation is very critical, and as the artist I’m not so concerned about it being done in a particular way. The sculpture is quite strong, people are very curious about it, it sits static in the space but we might be able to play the compositions. In Paris we’re working now with the Palais de Tokyo and the researchers and writers and the team connected to that institution. We're thinking how we’re going to activate it and how many times and usually those sorts of answers usually come down to how much the institution wants to employ musicians. The thing is, I want this work to make work and continue to make work – to be alive and channel and flow resources, so then as collectives we can start to talk about how this feels and what’s going on in the world. So in Paris I’ve asked them to research birds that are critically endangered and we are getting together a book of those calls and we’ll have to sit down with the musicians, once we’ve formed the ensemble and see if they are then able to produce the sound on the strings.

I’m kind of curious to see if it will work because the curlew has a particular call, people are like “what the fuck was that!”, on the island it’s very weird and spooky, and I haven’t yet listened to the birds in France. Also the sculptures themselves are really varying in their surfaces and textures and we can potentially, with some great musicians, bring it to life – I’m open.

MK: That’s the magical part of collaboration is having people from all backgrounds bringing their own contributions, collectives debunk the myth of the singular ‘genius artist’ and that is only really done through collaboration in community

MC: All art is collaboration. We shouldn't fool ourselves, the sooner we knock down the wall of the individual and the sooner we scrap this idea, the better chance we have of surviving. Because it’s a complete fabrication and it’s a complete construct.

MK: Speaking of community, you work a lot with public art, what sort of choices do you make when deciding where to present the art?

MC: For me, as a Quandamooka person, I’m always really mindful of where I am, and we’re getting better at understanding this culture knowing and practice of being present. Thinking about a lot of things at once and then also looking at what’s right in front and being able to tune into histories and energies, rivers and natural environments so you can receive the energy of the space. So when I go somewhere or when I’m invited somewhere to make something I make sure I’m really open to receiving what is there and listening to who is there and perhaps finding out things that are uncovered and perhaps things the dominant culture don’t want to talk about, but marginalised people want to talk about – so tuning into those discussions and making work that makes these things visible.

It’s the complexity of life that makes things beautiful and the quest to control to make things subordinate, quiet and homogenous is very dangerous, basically that’s when we just start to see death everywhere and the human spirit dwindles. So my work is always about trying to make space for the other, so we can understand complexity or just sit with it.

MK: That’s very beautifully said, a way of grounding someone into the present moment.

MC: Yeah, public work can also be very authoritative, the way advertising is authoritative. I understand the power of semiotics and how the built environment shapes the way we feel about each other, so I look at those sensibilities and strategies and then subvert them, try to co-opt them for good – I guess those words ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are problematic, but co-opt them to question everything.

It’s very important to question everything.

MK: I feel like that’s a large part of my project, being more aware of the space you enter, like you mentioned before about noise pollution and white noise, and its effect on the human condition.

When you’re approached by galleries to exhibit in their shows or commissioned works, are you conscious about what shows and spaces you’re a part of?

MC: I’m not a male artist, in terms of the institutionalised social hierarchy that is propagated, I’m not anywhere near the top but I’m still getting a look-in and invitations. I take my work very seriously and really care about people and really believe in the power of art so I always do my best, often when you get an invitation to a exhibition in a major public gallery the curator has already decided where you go and the politics and social hierarchies of prominence and position are not usually the artist’s decision.

MK: I guess connection, cooperation and communication with the curator and the other artists a that point is important

MC: Exactly, like that recent work at Tarrawarra, you go into that gallery and the north gallery is the most spectacular space. She was interested in another work on mine and when I read her rationale and her curatorial vision I put forward another work I’d done before with ice melting, she asked for drawings and we sat down to re-design the work in the space, and I had to be respectful to all the other artists because everyone wants to be in there.

A good curator will always work with the art and the space and that relation and it’s about the conversations of the artist’s works side by side as well as a whole. When there’s no overlap, there is a symphony of ideas that sing together in a visual language.

Rohan Rebeiro

Rohan Rebeiro is a Melbourne based musician with an electronic and acoustic percussive practice . His methodologies are both improvisational and compositional where he utilises percussion instruments to create poly-rhythms that are influenced by the space and those who occupy the arena. Over emails we exchanged thoughts on collaboration and location decisions.

MK: Firstly, could you explain the area of your art and music practice, and the method of your performances.

RR: I mostly work in the area of improvised and experimental music. My instruments would fall into the realm of percussion. I’m interested in the variety of tones that can come from instruments when played both appropriately and also slightly prepared, a combination of both approaches really. I like to practice rhythmic music ranging from traditional snare drum rudimental solos to North Indian tabla music. When I perform free improvised music I hope that elements of rhythmic training become manifested in the performance.

I take influence from people such as Akio Suzuki whereby I try to think of space as the instrument and really hone into the sonic nuances and musical potential of any given instrument or object. Some peripheral areas of my practice might be around cause and effect and deep listening.

MK: What are you conscious of when working with percussive objects?

RR: Attack, resonance, timbre and the ways in which each of those elements can be varied. I’d also consider how my hands/body can interact with the object to create a performance and how it might interact with other objects/instruments.

MK: Amidst lockdowns this year, you’ve have the opportunity to present a few shows, notably at the Meat Market pavilion alongside Grace Ferguson, Nico Niquo and E Fishpool, and also at Collingwood yards for Liquid Architecture’s Mono-Poly-March showcase, remembering those spaces, what differences did you notice in the two separate renditions?

RR: Both spaces were strangely similar in their beautiful reverberance. The Mono-Poly show was very intimate and I found the energy and space to be quite rich. When possible, I do like moving around a space and playing without microphones so the Collingwood Yards room was great for this – the frequencies seemed to bounce around the room really nicely. The Meat Market show was also incredible and on a much larger scale. I had a large circular area to perform in and the audience was extremely attentive. It was almost like a formal recital but with people laying around allowing themselves to fall into the sound on their own terms.

MK: I’m interested to know the process of choosing a space to perform, especially when collaborating with artists and performers, what sort of conversations surround the locations for your events?

RR:It can depend on what sort of show it might be and what the sound requirements are, but in general it currently feels nice to use non-traditional spaces for a performance. Having said that, the functionality of a music venue or club is incredibly valuable to any community.

MK: With the spontaneous nature of the performance, do you aim to embrace improvising, or does it lean to a critical approach of creating sound?

RR: I’d love to consider my practice as being something of a purely musical approach with little context or interrogation, but with improvised and experimental music there is a level of inherent criticality underpinning it I think. If I perform really well, I would probably call it music with some sort of primordial blessing… and if I don’t play as good, then I can contextualise it into some sort of sound art … haha just kidding! The critical thinking for me is there before and after performances but never really during. It all binds together. The performance should generally let go of any narrative if possible.

My Disco: https://mydisco.bandcamp.com/

Dylan Martorell

Focusing on collaborative and impromptu sound based art, Dylan Martorell’s research and work is conscious of the way in which sound is affected by changes in culture and geography. He has exhibited and performed nationally and internationally, as a solo artist and with socially-engaged methodologies. Through email exchanges, Martorell and I discussed the geographical decisions with his off-site works and how it provides an array of challenges and opportunities for spontaneity.

MK: Many of your art projects are situated outside of gallery spaces, what thought processes are involved in location scouting for your projects?

DM: It’s very dependent on each project and is also dependent on concepts of public space which varies greatly. I’ve loved working across South East Asia/ Indonesia, India /Taiwan as the concept of public space is quite different, compared to Australia the public life of the city is based outdoors and one space may be used for various activities during the course of a day. It’s easy to get access to outdoor public space and it’s where I feel comfortable.

I've always been on the edge of the art-world and have always found the most interesting situations happen when you place yourself in the world outside of the gallery space. The gallery based art-world is either geared towards creating products to sell or it is a very closed environment as far as demographic / audience is concerned. I am more drawn towards community arts/ working in schools etc as I feel like this is where art should live. This is highly reductive but it's what I’m drawn to, this is especially true when i am working overseas.

I think it’s a much more generous approach to try and immerse yourself in a local community and encourage interaction and play with the people who live in the area that you are working rather than catering to a closed arts based community.

Locally, my last series of projects have been focused on exploring green spaces with my 5km and 1Okm lockdown bubble so by default this is where the project has taken place. It was a project that tried to create a public artwork that was Covid Proof but still accessible to a diverse audience.

MK: Could you reflect on previous experiences of installing and presenting an artwork that had a strong sound aspect, and how did the space affect the artwork?

DM: The Kayak Orchestra which I worked on with Lichen Kelp and Jannah Quill was a great example of environmental impact on sound.

This was a performative event where a group of kayakers were part of a spatialised sound work which included kayaks incorporating portable speakers playing minimal electronic pulses, and kayaks pulling various floating sound sculptures. The idea was to create a spatialised , constantly shifting bed of sound which was designed to help you focus on the pre-existing sound of the environment of Lake Tyers. The great thing about this project is that the environment played such a major role in the sound world. The sculptures reacted to varying conditions of water movement, wind and rain; different times of day resulted in different environmental sounds such as the mullet jumping and the swallows catching insects in the evening , birdsong and different insects competing with the sound of watercraft during the day.

The thing I am most excited about re-exhibiting and performing sound work is the creation of various spatialised , shifting sound environments that inhabit their own space but co-exist together as a polyrhythmic sonic space.

I also love setting up my robotics in various public spaces and using found materials as the percussive elements. This incorporates the sound world of the public space as well as the sound of the found materials that live in the space. Again it’s most exciting when the performance is given over to the public.

https://www.dylanmartorell.com/

Part 4: Visualisation

The result is an imperfect, idyllic, incomplete, unprocessed, unfiltered, rough and fragmented visualisation of the perfect space for art. The acoustics of the excavated room are trapped in a tomb of concrete walls, carpeted flooring and a vast ceiling insulated in soft and porous foam. Every echoing footstep is absorbed; a library silence, meditative, senseless, enigmatic.

To imagine this space is to obscure all previous knowledge of the interaction between art institutions and the human senses. A Companion for Gallery Listening is to be accessed and exercised in order to enlighten the holistic experience of art viewing

.

This project was completed under mentorship of Anna Parlane, Joel Stern and Hannah Mathews as apart of my 2021 Graduate project for a Bachelor in Fine Arts (Art History and Curating specialisation)

https://listeningcompanion.wordpress.com/

Reference List:

Textual

Fowler, Michael. "Sounds in Space or Space in Sounds? Architecture as an Auditory Construct." Arq (London, England) 19, no. 1 (2015)

Gallagher, Michael, Kanngieser, Anja, and Prior, Jonathan. "Listening Geographies." Progress in Human Geography 41, no. 5 (2017)

Kanngieser, Anja. "Geopolitics and the Anthropocene: Five Propositions for Sound." GeoHumanities 1, no. 1 (2015)

Kelly, C., & ProQuest. (2017). Gallery sound.

Schafer, R. Murray. The New Soundscape : A Handbook for the Modern Music Teacher. Don Milles, Ont.: BMI Canada Limited, 1969.

Schafer, R. Murray. The Tuning of the World. 1st ed. New York: Knopf, 1977.

Smith, Robin James, and Hetherington, Kevin. "Urban Rhythms: Mobilities, Space and Interaction in the Contemporary City." The Sociological Review (Keele) 61, no. S1 (2013)

Watson, Aaron, and Keating, David. "Architecture and Sound: An Acoustic Analysis of Megalithic Monuments in Prehistoric Britain." Antiquity 73, no. 280 (1999)

Non-textual:

Katsalidis, Nonda. Museum of Old and New Art. 2011. Hobart, Tasmania.

Bochner, Mel. Measurement Room. 1969. Installation. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich

Kelly, Mary. Post-Partum Document. 1973-1979. found material

Gothe-Snape, Agatha. Wet Matter. 2019, various .wav files loaded onto Pixel smartphone, Sounds in Space mobile app, audio transmitting devices, custom-made harnesses, wall painting, architectural interventions, dimensions variable. Monash University Museum of Art

Shutz, Stephen. Sound Library. 2010. ZIP file